Composition versus Music

I’m delighted to welcome Dr Kevin Malone to the site, who kindly consented to write the first ever guest post here! Kevin is Senior Lecturer in Composition, and former Head of Composition at the University of Manchester. He is writing here in a private capacity, in response (initially) to the Alex Ross article mentioned below. You can find out more about Kevin’s work at his website, www.opusmalone.com. Kevin and I hope you enjoy the article… do let us know what you think!

We confuse “composition” with “music”. Not all composition is a subset of music. Their relationship can be described in a Venn diagram whereby the circle “Composition” partly overlaps the circle “Music”: a joyful intersection in the middle. This is where the composer-as-artist has succeeded in creating a musical work which, on its own audible terms, has communicated its whole essence to listeners. Compositions which cannot manage this are, well, just compositions.

Alex Ross’s Guardian piece of 28 November 2010 beckons audiences to stay in their seats and enjoy – or ride out – the sonic offerings of modern composers. He states that part of the problem audiences face are these composers’ “new vocabulary of chords and rhythms”. Modern works hardly offer a vocabulary; instead, composers mostly use a lexicon, one which changes from composition to composition, and usually within each composition, and very swiftly.

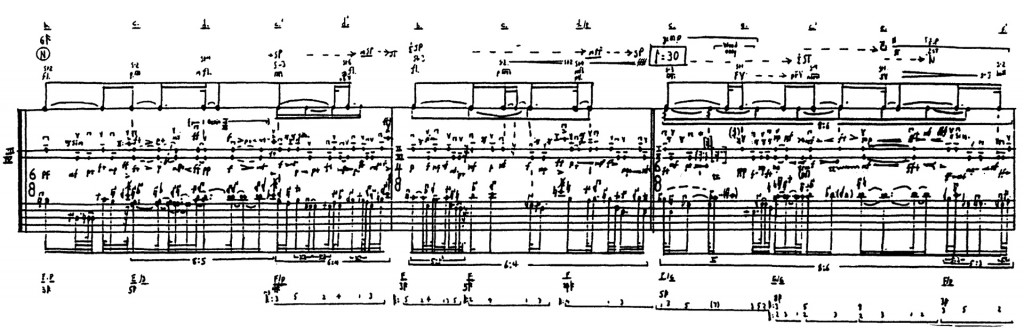

The heart of the problem is dissonance, but not the dissonance we normally think of (which some may call “atonality”). Audiences are faced with rhythmic, textural, timbral, dynamic, registral, structural, melodic and harmonic dissonances. These parameters often undergo rates of change far beyond the ability for humans to perceive and process them. The failure for audiences to hear patterns and connections within the composition is not their fault: it’s due to a lack of understanding of the psychology of listening on the part of composers. Instead of multiple simplicities of combining tones and controlling the rate at which they can be perceived and transformed, composers deploy an array of athletic techniques which demonstrate intellect, knowledge, pedigree and a distinctiveness from other works. In short, musical complexity – the careful combining of tones in relation to perceived listening – is replaced with complicatedness.

The emphasis is shifted away from listening to the work to, instead, THE WORK, a position which draws attention to the work’s author, and to the decisions made in creating the piece, rather than the musical work’s own needs being fulfilled in order to sound decision-free; that is, for the work to sound autonomous, free from the creator’s decision-making process.

Now, there is no problem with a composition occupying the “it’s my work” realm, a rather closed world in which the listener has to journey into the composer’s personal space to find out the what and why of the composition. No doubt the programme notes will reveal the intellect and inspiration behind the composition, complete with a list of credentials and awards. But surely, the music itself should harbour its own credentials, revealed through a self-contained, self-sustained delivery of a superior psychological understanding of musical sound upon the listener.

When it fails, it can be spectacular. In a Sony recording of Stockhausen’s Klavierstück No.2, I, the composer provides extensive liner notes, complete with details of the pianos used, recording equipment, numerous specific microphones, dates and venues, very precise times of day for recording and editing and even the changing humidity. No data is left unchecked. But what Stockhausen fails to notice is that Aloys Kontarsky’s playing and his own chosen edits are so wildly off target from the exceptionally-detailed notated data of the piano score that the timing is altered by 50% by the end of the first page alone.

Performers must speak with many parameter-change relationships, or “languages” – tonality, modality, atonality, extended techniques – and must learn performance practices to include ornaments, phrasing, etc. Modern composers are really only allowed one, if we’re to be taken seriously: extended atonality. The main argument is that the composer is not being original by not creating something new with a unique “vocabulary” (back to that misnomer again). This presupposes that originality itself is more valuable than excellent craft, canny slights of hand, wit, and fully deploying the psychology of the sonic communication to the listener.

How do we come to love music? It’s almost entirely through tonality, patterns, specific time-base events we can rather accurately reproduce in good-size chunks in our memory. We don’t initially come to “love” it through Stockhausen or Birtwistle. However, through them, we may become “interested” in music aside from “loving” it. Ligeti, Penderecki, Ives, Rochberg and Crumb did it for me. We come to be fascinated, intrigued, challenged by the compositions they produced, but this interest is held as a measure to what we already knew: the careful sonic-parameter control awareness of Beethoven, Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Ravel. Never-mind that critics of their time occasionally slated their works as the products of madmen (men, always men): the tonal relationships and patterning were certainly in place and audibly so. If the critics didn’t like them, then that was a matter of aesthetics, not changing-parameter overload. Musicianship training hadn’t yet overridden innate musicality.

What if the other time-based arts – film, dance, theatre – had their parameters of perception change as swiftly as those within much modern music? Could a film or a play remain comprehensible if its dynamics, timbres, colour saturation, visual editing, etc. all change at the rate of, say, that Klavierstück? Why DO composers write so many notes, with such densely-changing parameters?

The main reason for this is because, by using so many notes, composers are covering their genitals. They don’t want to be seen as exposed, easily understood, emotional and available for communication. Composers want to be mysterious to non-composers.

And consequently, the compositions resulting from this stance are obtuse, difficult, deflective and very demanding on their own terms. Who’d want to be in a relationship with someone like that? Perhaps that explains why the average concert-goer doesn’t like us, and many just walk away.

I just now came across this page, which I had not seen before. Although I am grateful for the mention of my work, I’m afraid you have misunderstood my intentions and music entirely. I am a professional cellist as well as a composer, and I have performed this piece, as well as my solo piece Clairvoyance, as well as a fairly large repertory of recently-composed works I call The New Cello well over a hundred times in at least 12 countries. The fact that I am performing all these works for live audiences should really lead one to some caution about making the sort of broad, prejudiced generalizations that I see here.

My aim in writing this piece had pretty much nothing to do with expecting the listener to keep conscious track of minute differentiations of the sort the Milton Babbitt, for example, specialized in. The entire piece is in fact a continuously unfolding melody. The constant changes in dynamic an texture and timbre have much more to do with my love of non-Western traditions of music than with fidelity to a row. Owing to the layering of actions, it is almost inevitable that each performance will be slightly different, which satisfies me a great deal, because I am committed to an aesthetic of live performance. This also contradicts your main claim.

It’s really not hard to look this stuff up; I’ve co-published ten books and an online journal. You are free, of course, to like or dislike my music. But if you’re going to criticize it, how about making the effort to know what you’re talking about.

P.S. I also composer tonal music, music for student ensembles, and so forth. Characterizing my aims the way you have is simply wrong-headed.