There’s something about Ludwig

In the last few weeks, I seem to have spent a lot of my time thinking about Beethoven. In addition to a lovely session of Music Talks in South Kensington, where I had a live quartet on stage to help me explain the inner workings of the A minor String Quartet Op.132, it’s that time of year for him: running a nineteenth-century music course at Middlesex University does inevitably involve a lot of talking about, analyzing, philosophizing about and ultimately writing essays on… you guessed it… LvB.

When I first arrived at university, and had some half-baked notion of becoming a school teacher, I remember the idea of teaching the same thing, every year, being a serious point in the minus column in considering this vocation. So as October rolls around again, and I find myself teaching a load of Beethoven sessions again, I am – again – struck by just how not remotely bored I am with any of his music. In fact, I feel like I get more enthusiastic about it, more fascinated by it, with each passing year. No wonder some of my students think I’m a little cracked.

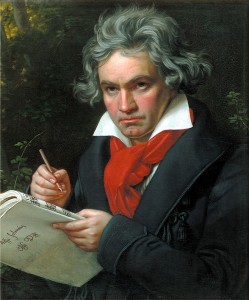

I recently stumbled across a brilliant little video about Beethoven by Tom Service. He’s sitting at his desk in his home, trying to capture – in just three and a half minutes – what it is about Beethoven. The man, the legend, the hair and the general sense of grumpiness… the tragedy and triumph… the endless wonderful pieces of music. The fact, ultimately, that Beethoven was a person, it was a real human being who wrote these pieces which we simultaneously hold so high in our cultural canon, and treat as if they are part of the everyday because they are so familiar.

I recently stumbled across a brilliant little video about Beethoven by Tom Service. He’s sitting at his desk in his home, trying to capture – in just three and a half minutes – what it is about Beethoven. The man, the legend, the hair and the general sense of grumpiness… the tragedy and triumph… the endless wonderful pieces of music. The fact, ultimately, that Beethoven was a person, it was a real human being who wrote these pieces which we simultaneously hold so high in our cultural canon, and treat as if they are part of the everyday because they are so familiar.

Ultimately, like everything, it’s no good having someone telling you that You Should Appreciate How Great Beethoven Is. I mean, that’s like your parents telling you that you should sit still and be quiet when that’s the last thing in the universe that you want to do. Pretty much the only reasons you’d do either would be blind duty, fear or guilt. In the case of all three motivations, crucially, you wouldn’t understand why. Why should you appreciate Beethoven? The only way you can really appreciate him is to have a crack at understanding him yourself – just as the only reason you’ll appreciate why your parents want you to sit still and be quiet is at the point when you actually figure out what a quiet carriage on a train is for… and you have to question the decision of the person who either put a bouncy three-year-old in the quiet carriage, or made Beethoven-appreciating noises at you, in the first place, if you were never going to understand the reason why.

It really is true that teachers learn a lot through teaching. That’s not just to do with the feedback of the students, but can also be to do with the simple fact that, if you have to look over something intensely and repeatedly, you will find new things. You might have time to do a bit more analytical digging in the second year; by the third, you will start spotting clever tricks of harmony, unusual textures, daring new motives and orchestrations. For you, too, will be understanding more and more deeply the brilliance of the thing before you, rather than taking other peoples’ word for it. And I’ve found that I’ve also developed a more detailed appreciation of what else was going on at the same time. If you don’t have a sense of the general sound-world of 1803-4, it’s harder to appreciate why the Eroica Symphony was so daring and revolutionary. If you have a clearer idea of the sort of philosophizing going on around instrumental music in the first few decades of the nineteenth century, the choral finale of the Ninth Symphony doesn’t strike you as being anything like as audacious and innovative. Thematic recall between movements; weird and wonderful tonal regions (in the striking words of one critic writing on a late string quartet, ‘the white stripe of the milky way’); energy and rhythm and musical daring… Beethoven is amazing. Amazing man, amazing music. It doesn’t make him perfect; he could be a complete menace and wrote a few things that are either not great or decidedly boring. But it’s not about obtaining a perfect score on some kind of imaginary (and impossible) scale. It’s about vision, craftsmanship, and artistry. He had these things in bucket-loads.

So I’m loving my annual Beethoven journey – loving finding new things and sharing the excitement of it all with my students (and indeed anyone else who will listen). My goodness, he was clever! Want to know how to write a sonata form movement? Break a sonata form movement? Completely re-conceive of a sonata? He’s your man. It’s difficult to find a way to him, sometimes, past all the hype and the scowls and the tiny plaster busts… but it’s worth it. I promise you. And it’s all online for you to enjoy! You don’t even need to have your own court orchestra any more – pretty cool, eh? Spotify, YouTube, IMSLP and a heap of other sites will provide you with your very own library of scores, recordings, and videos. You will find yourself dancing around the room and pointing open-mouthed at the score, and flicking backwards and forwards to find the point where you’re sure you’ve heard that theme before. How amazing is it that he can still have us doing this, 200 years later? Go on, give him a try. He’s pretty awesome, when you get to know him.

Pingback: Piano News Roundup: October 24 » Piano Addict